Supporting Instructional Alignment in Science of Reading Implementation

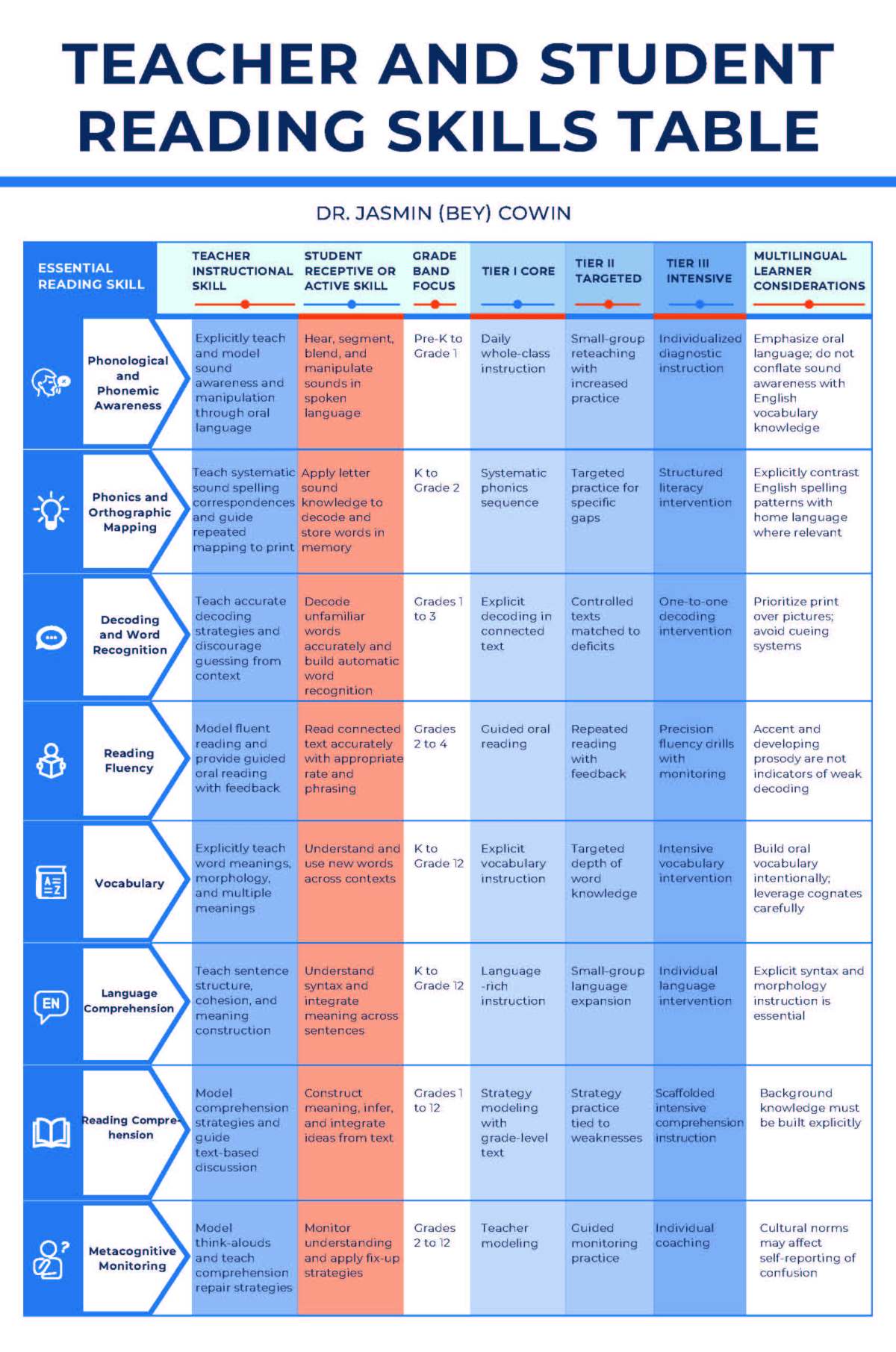

The Teacher and Student Reading Skills Table is intended to support educators in aligning instructional practices with evidence-based literacy research. Rather than operating as a scope-and-sequence, the table aims to clarify instructional roles, student skill development, grade band emphasis, tiered supports, and multilingual learner considerations. When used deliberately, it may help reduce ambiguity in Science of Reading implementation.

Foundational Skills: Phonological and Phonemic Awareness

The chart places phonological and phonemic awareness within oral language instruction, with emphasis in Pre-K through Grade 1. Teachers are expected to model and teach sound awareness and manipulation, while students work to hear, segment, blend, and manipulate sounds in spoken language.

An important implication of this framing is that phonemic awareness instruction does not rely on English vocabulary knowledge. For multilingual learners, sound awareness and lexical knowledge represent related but distinct competencies. Instruction that separates these skills may support more accurate interpretation of student performance and instructional need.

Across tiers, the chart suggests that increased intensity should involve additional practice and diagnostic attention rather than a shift to alternative activities.

Phonics and Orthographic Mapping

The chart situates phonics and orthographic mapping primarily in Kindergarten through Grade 2. Teachers provide systematic instruction in sound–spelling correspondences and guide repeated connections between print, pronunciation, and meaning. Students apply letter–sound knowledge to decode and gradually store words in memory.

This progression reflects the view that orthographic mapping develops through repeated, accurate decoding rather than exposure alone. The tiered structure emphasizes that students who experience difficulty may benefit from greater explicitness and structured practice rather than compensatory strategies.

For multilingual learners, contrastive analysis of English spelling patterns and home language orthographies is presented as an important instructional support when integrated within explicit phonics instruction.

Decoding and Word Recognition

In Grades 1 through 3, the table highlights instruction focused on accurate decoding strategies. Teachers guide students to attend to print, while students practice decoding unfamiliar words and building automatic word recognition.

The multilingual learner guidance encourages prioritizing print-based information and limiting reliance on pictures or context cues. This emphasis aims to support efficient word recognition development and to reduce instructional practices that may interfere with decoding growth.

Tiered supports in this domain are intended to reflect differences in intensity and instructional focus, informed by observed error patterns and student response to instruction.

Reading Fluency

Fluency instruction is emphasized in Grades 2 through 4 and is described as involving teacher modeling and guided oral reading with feedback. Students work toward reading connected text with increasing accuracy, rate, and phrasing.

The table notes that accent and developing prosody are not necessarily indicators of decoding difficulty. This consideration may help educators interpret fluency data more carefully for multilingual learners and distinguish between linguistic variation and skill-based needs.

Across tiers, fluency instruction becomes more targeted and closely monitored, with attention to maintaining a connection to underlying decoding accuracy.

Vocabulary and Language Comprehension

Vocabulary and language comprehension are presented as ongoing instructional priorities from Kindergarten through Grade 12. Teachers explicitly address word meanings, morphology, syntax, and sentence-level cohesion, while students work to understand and use language across contexts.

The chart’s separation of vocabulary, language comprehension, and reading comprehension reflects the view that these domains develop through related but distinct instructional pathways. For multilingual learners, intentional oral vocabulary development, explicit syntax instruction, and careful use of cognates may support language comprehension growth.

Tiered instruction in these areas often emphasizes depth of understanding and structured language practice rather than reduced linguistic demand.

Reading Comprehension and Metacognitive Monitoring

Reading comprehension instruction begins in early elementary grades and extends through secondary levels. Teachers model comprehension strategies and guide discussion grounded in text, while students practice constructing meaning, making inferences, and integrating ideas.

Metacognitive monitoring, introduced in Grade 2 and beyond, involves teacher modeling of think-alouds and instruction in comprehension repair strategies. Students develop the ability to notice breakdowns in understanding and apply appropriate fix-up strategies.

The table acknowledges that cultural norms may influence how students express confusion, suggesting that educators consider multiple indicators of comprehension.

Multi-Tiered Systems of Support and Instructional Coherence

The tiered structure outlined in the chart is intended to support instructional coherence across Tier I, Tier II, and Tier III. Core instruction provides the foundation, while targeted and intensive supports increase explicitness, practice, and responsiveness.

This framing positions MTSS as a system for adjusting instruction based on student need rather than as a static placement model.

Conclusion

I believe the value of the Teacher and Student Reading Skills Reference Table lies in its attempt to make instructional expectations more explicit across reading domains, grade bands, and tiers of support. When used reflectively, it may support instructional planning, collaborative decision-making, and more consistent implementation of Science of Reading principles across diverse classroom contexts.